BACK

TO MY INDEX PAGE

MY TIMES

AT HARRISON & SONS LTD. 1956 to 1966

CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION

2. HISTORICAL NOTES

3. THE HIGH WYCOMBE

FACTORY HISTORY.

3.1 The Original factory

Buildings

3.2 The

First years of Production

4. LIFE AS AN APPRENTICE

1. INTRODUCTION

I am writing this not only to record

this part of my life, but also to provide a record of the High

Wycombe factory at the time 1956 to 1966.

There does not seem to be a record like this as far as I can

find on the Internet, so I bear this in mind as I try to

remember the facts as I knew them.

The main printing process at the factory was Rotary

Photogravure, called Rotogravure in USA or simply "Gravure".

Existing records mostly concentrate on the postage stamp

printing work of Harrisons using the gravure process, but the

Wycombe factory expanded the commercial printing side at this

time.

General gravure catalogue and magazine printing was expanded

as well as specialist printing of art reproductions for the

National Gallery and also laminate printing of "Formica" type

wood grain surfaces. There was also some limited Letterpress

process printing.

All this made High Wycombe an extremely versatile gravure

printing works, capable of undertaking any variation of the

process. This was particularly important when the first

British colour pictorial postage stamps were printed.

It incidentally provided me with a superb apprenticeship to

the process which stood me in great stead through my career

including R&D and eventually Lecturing.

I hope I can do justice to this wonderful family firm which

deserves a special place in the history of printing and the

Rotary Photogravure process.

I recently received an email from Daniel Mark

Harrison as follows;

"Dear

Mr. Barcock,

I wanted

to reach out to you personally and thank you for putting online

your autobiography, particularly the wonderful things you said

about Harrison & Sons.

It was with profound pleasure and interest that

I happened to come across your autobiography online the other day

while searching for information about Harrison & Sons to show

my fiancee,

when I was telling her about the firm that used

to belong to my family.I am Daniel Mark Harrison, 34

years old, and born on 1st

July 1980, I am as such the oldest of the

9th. generation of Harrisons, son of Mark

Ernest Harrison, who is

son of the late Ernest Handyside Harrison, with whom personally

and/or his generation you will have worked. Ernest was the

youngest of his brothers, the oldest of whom was Nigel.

I

am not sure to what extent you have kept in touch with any of

the family, but I wanted to extend my personal gratitude to you

for the enjoyment I experienced in reading about the perspective

of someone who was not from the family but

who had rather trained and worked there. In return I thought it

would be nice if I sent you a history of the family in the years

after the firm lest you do not know what happened - if only to

quench

what might be a mild curiosity".................................

A full transcript of this email is reproduced, with his

permission, in my Autobiography

Documents Page.

I am very grateful to Daniel for allowing me to do this as it

adds valuable information and authenticity to my account and

brings it up to date with the Harrison family history.

BACK TO CONTENTS

2. HISTORICAL NOTES

The firm of Harrisons can be traced back to 1750 and Thomas

Harrison b. 1723, d. 1791.

I have this information from a book "Harrison. A Family

Imprint" published to commemorate the bicentenary in 1950.

I can't remember exactly how I came to have this book. Whether

we were all given copies after I started in 1956, or perhaps

my Uncle Jack Barcock gave me a copy as he was in it.

In either case I treasure my copy now as it has pictures of

most of the journeymen printers who taught me the trade.

Now I also find that I enjoy reading the history of the firm

as I can appreciate the unique place it occupied in printing

and the history of London itself.

Most of my knowledge of the firm before I joined comes from

that book and my Uncle Jack. I will explain his great

contribution to the firm in the coming chapters.

The very first Harrison known to be a printer was Richard who

was listed in the 94 freemen in the Charter of the Stationers'

Company of 1537.

On a visit some years ago to Stationers Hall I saw that

Harrisons were past Masters of the Stationers Company on the

wall plaque of past Masters.

The Harrisons certainly have their place in London's history.

Two of the company Chairmen have been knighted:

Sir Cecil Reeves Harrison in 1918 and Sir Guy Harrison in 1951.

Both served as Masters of the Stationers Company.

I recently found reference to the connection with the Stationers

Company in an old Harrisons house magazine, 'Review' of June 1961.

An article entitled "A Family Name", apparently an extract from a

a Stationers Company article, contains this section;

"Many well known and notable names in the Printing trade are

recorded on the Livery Roll of the Company and over many years

one name appears rather often, the Family name of Harrison, a

family that can justifiably take pride in the knowledge that

since the year 1750-the year of foundation of the present firm

of Harrison and Sons Limited-seven members bearing the name

Harrison have been elected as Master. Their names and the year

of office are set out as below;

1784 THOMAS HARRISON 1828 JAMES

HARRISON 1900 JAMES W.

HARRISON 1928 CECIL R.

HARRISON 1930 EDGAR E.

HARRISON 1947 VICTOR B. HARRISON

1948 BERNARD GUY HARRISON."

The article then goes on to name a further 9 family members

who are Liverymen of the Company. It continues;

"Apropos of numbers it was stated by the late Ralph D.

Blumenfeld (Deputy Master) at the Livery Dinner of 1934

that if a new Livery Company were created it should be called

"The Worshipful Company of Harrisons," a delightful tribute to

the family of that name."

Following the first Richard, Thomas Harrison, born in Reading,

really started the printing dynasty after serving his

apprenticeship with the "Confidential Government Printer" Office

in 1738.

He was followed by his brother James in 1743, both serving 7 year

apprenticeships. I realise now why I was privileged to also enter

the trade as an apprentice with Harrisons and why they treated

their apprentices so well. That connection with the Government in

positions of trust no doubt secured Harrisons future as Government

printers.

It is ironic that the last Harrison in print was also Richard who

departed the firm when it was taken over by Lonrho in 1979. In

1997 it was taken over by De La Rue International Ltd., and the

High Wycombe factory eventually closed down. It was tragic to see

it become derelict and for years I drove by the side entrance I

used to go in by in Hughenden Avenue where the main entrance had

the "By Appointment" Royal Coat of Arms. Now the site has been

razed to the ground and it it just a heap of rubble to become

housing I expect.

But the name of Harrison as printers lives on in documents such as

this and The National Archive.

We are all come to dust eventually and all we can hope is that, in

the words of Longfellow " ... leave behind us footprints on the

sands of time". Perhaps what follows might qualify as one

footprint.

3. THE HIGH

WYCOMBE FACTORY HISTORY.

3.1 The

Original factory Buildings

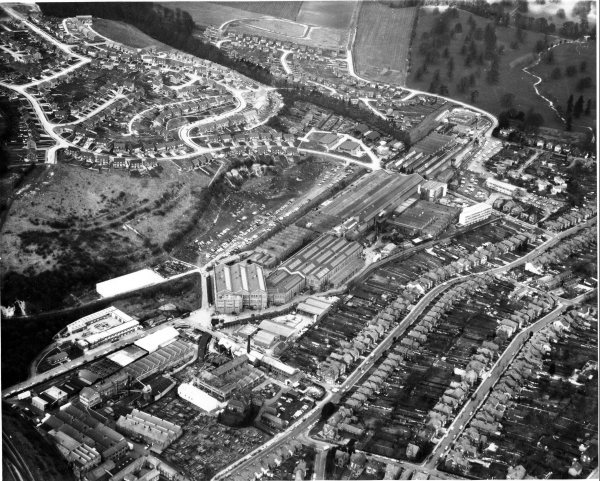

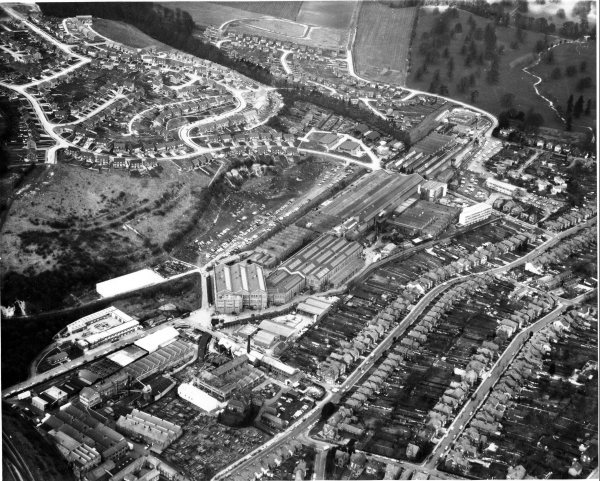

I have found it difficult to find a photograph of the

Wycombe factory before it was abandoned but I discovered this

aerial view in the Wycombe Library Archive. It appears in the

"SWOP" website of WDC and I am grateful for their permission to

include it here;

Harrisons

is

at

the

right top next to Hughenden Park where the trees and stream can be

seen.

Harrisons

is

at

the

right top next to Hughenden Park where the trees and stream can be

seen.

The main factory in the view is Broom & Wade, later

BroomWade, who built air compressors but most famous for

building tanks in the WW2. These were tested on the

steep slopes above the factory. Harrisons was just the section

above where the road divides the factories, Hughenden Avenue.

The

Harrison

factory

section

is here;

Not a very clear view, but enough to give an idea of the

pleasant location near the Park.

It is stunning to reflect here on the fact that some 2000

workers were employed at BroomWade and around 750 at Harrisons,

and now there is nothing left of the factories.

They were protected from bombing by the climate during WW2 as the

Valley was often covered in mist. I see that now from my house in

Green Hill overlooking the Valley, but not so often now there is

no factory smoke. At the bottom of Green Hill a farm, Asperey's,

had a farmhouse built over the site of a German or returning RAF

bomber crash. Fred Asperey lived on top of an incendiary bomb

which was discovered when the farmhouse was demolished! We used to

take our kids to see the hens and pigs in the farmyard. They had

cows which supplied local dairies.

As a result of searching for these pictures I made contact with

Peter Tozer who in retirement has been researching Broom and Wades

history and gave me information about the firm and the following

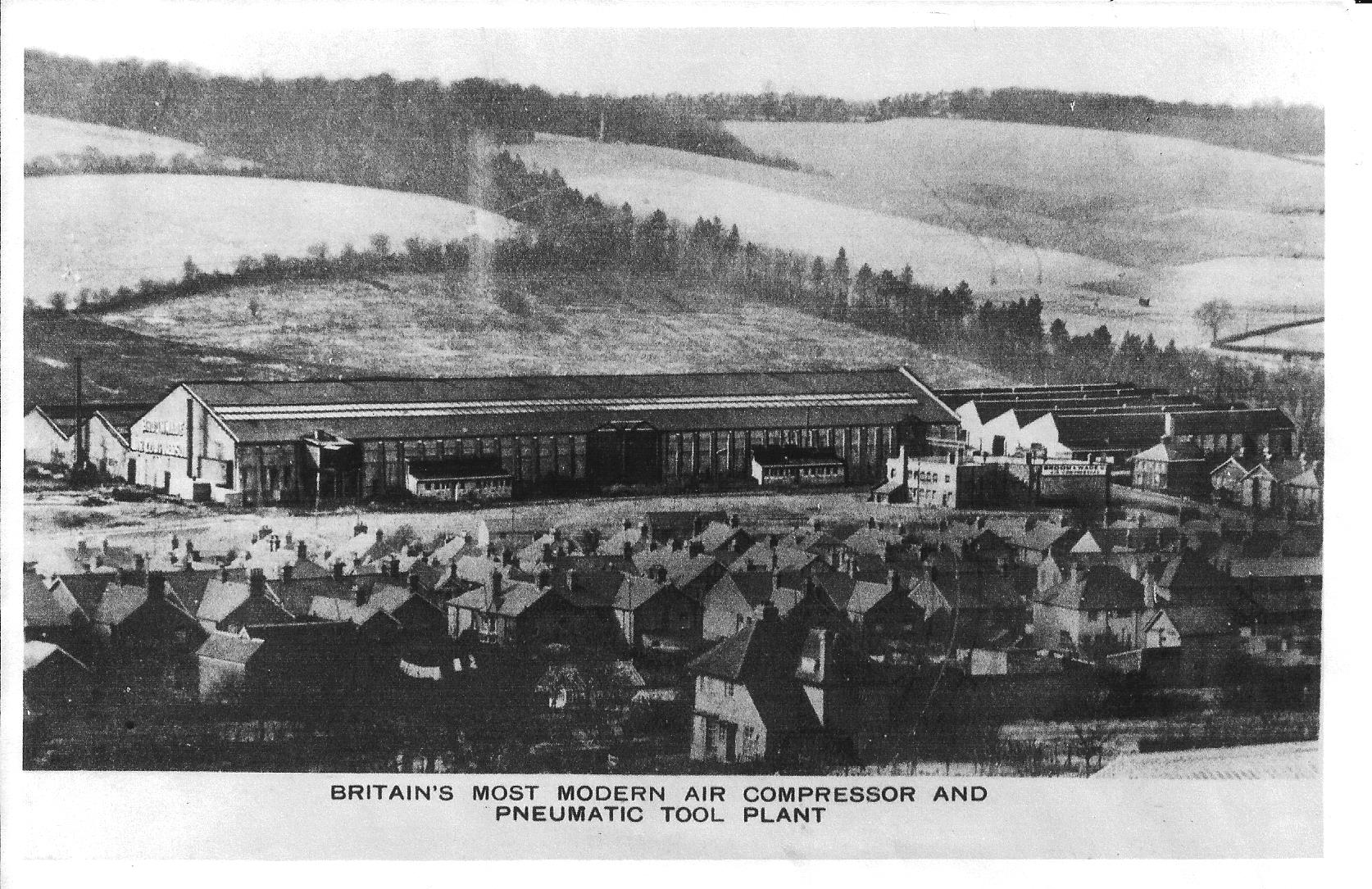

fascinating views of the original factories which I include here

with his permission.

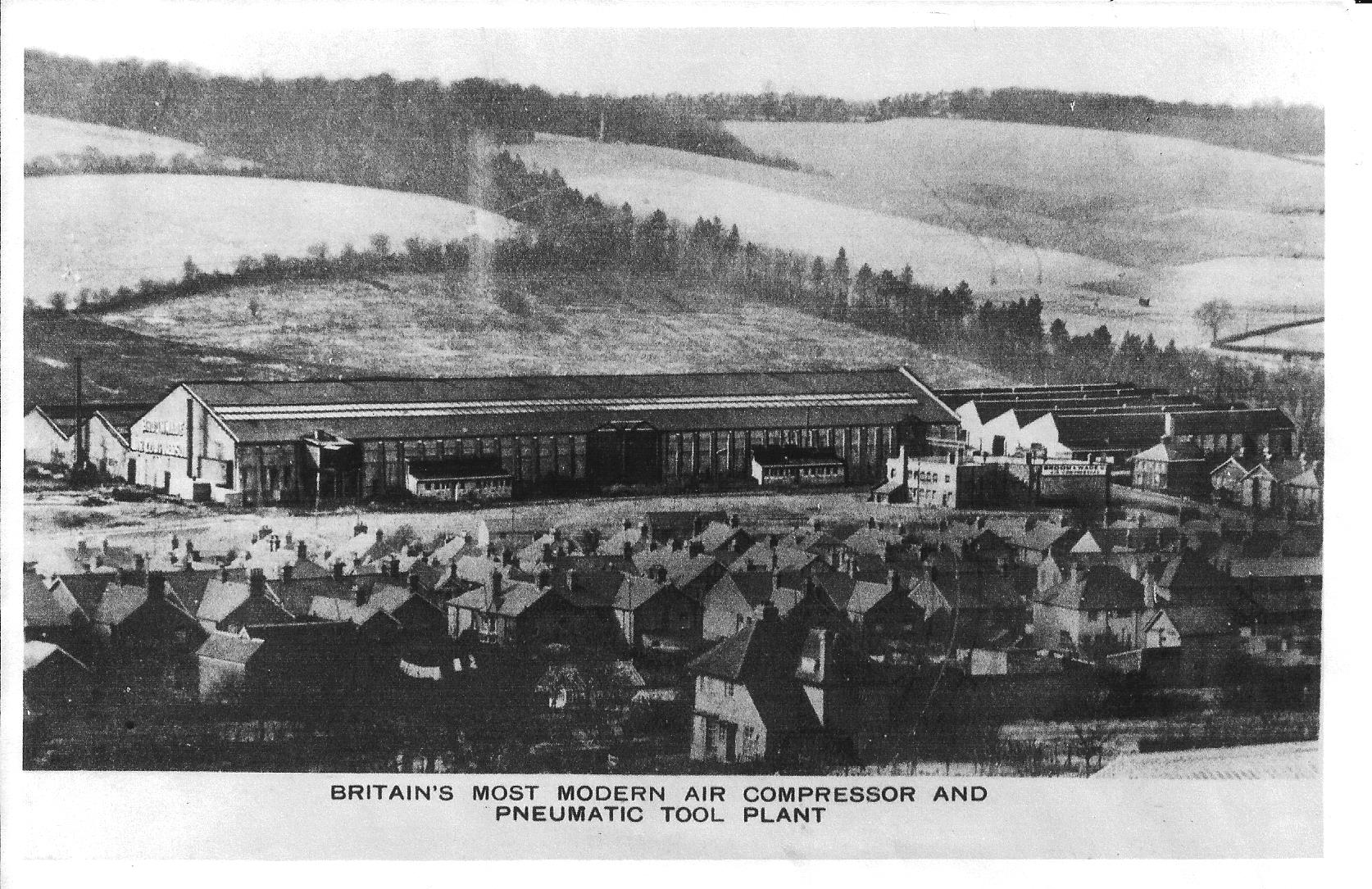

These I understand from

Peter Tozer and some research I have done were the sheds used by

the "Wycombe Aircraft Constructors" company. These date from at

least 1917 when the company was set up to manufacture parts for

aircraft, particularly in WW1, by George Holt Thomas of Wycombe.

He set up a company called Airco in Hendon in 1912 and employed

the famous Geoffrey de Havilland as chief designer.

These I understand from

Peter Tozer and some research I have done were the sheds used by

the "Wycombe Aircraft Constructors" company. These date from at

least 1917 when the company was set up to manufacture parts for

aircraft, particularly in WW1, by George Holt Thomas of Wycombe.

He set up a company called Airco in Hendon in 1912 and employed

the famous Geoffrey de Havilland as chief designer.

I found this information in the High Wycombe Society Newsletter

of Summer 2012 in an article by David Scott.

Aircraft manufacture then being of wooden construction could make

use of the woodworking skills of the furniture makers. I have

discovered that the factory at Wycombe probably never went into

production and the sheds were obtained by Broom and Wade.

This photograph shows the sheds eventually obtained by Harrisons

at the right hand end. They are the white triangular shaped sheds.

The road between them and the Broom and Wade sheds is Hughenden

Avenue.

The houses in the foreground are Hughenden Road and Conningsby

road.

I look over this view from my house and see the fields and the

Disraeli Monument on the far hill in the top centre.

Geoffrey de Havilland was actually born on 27 July 1882 at Magdala

House, Terriers, High Wycombe, nearby to where I live.

BACK TO

CONTENTS

3.2 The First

years of Production

The earliest reference I have to the factory at High Wycombe is

from the book "Harrison. A Family Imprint" mentioned above. This

was as follows;

" The Company's development of photogravure was so successful that

in the year 1933 the Post Office decided to adopt this very modern

process for the manufacture of all the British postage

Stamps up to the 1s. denomination"........"A vacant building was

secured at High Wycombe and a new industry was established in this

ancient borough of chair-making fame".

So Harrisons took over the vacant sheds in the picture above in

1933 and developed them for photogravure printing. My Uncle Jack

was there at the beginning because he had joined Harrisons at the

Hayes factory and helped set up the photogravure process he

learned from his time at Clarke and Sherwells of Northampton. He

did most of the process stages but settled eventually as the

foreman of the planning department where glass page photos were

planned into pages. This was a key job as it had to use schemes to

suit the particular printing machines.

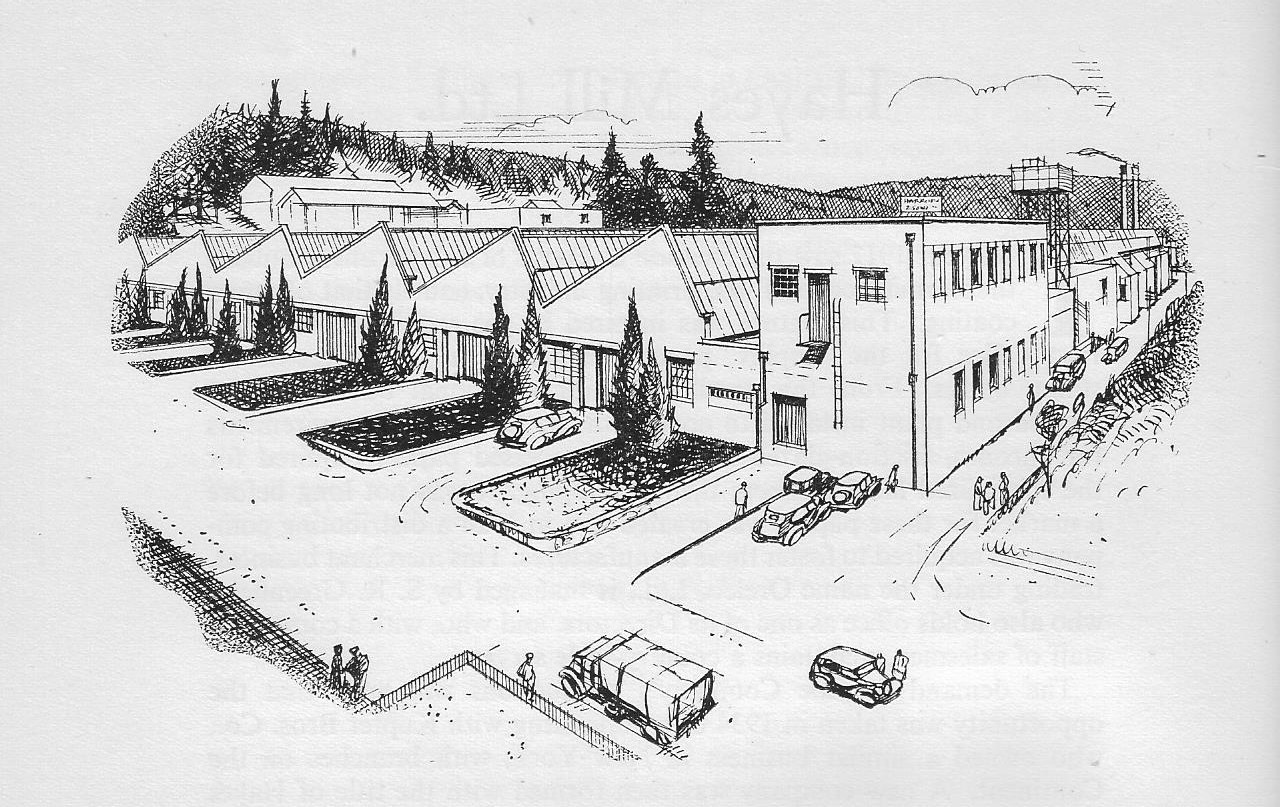

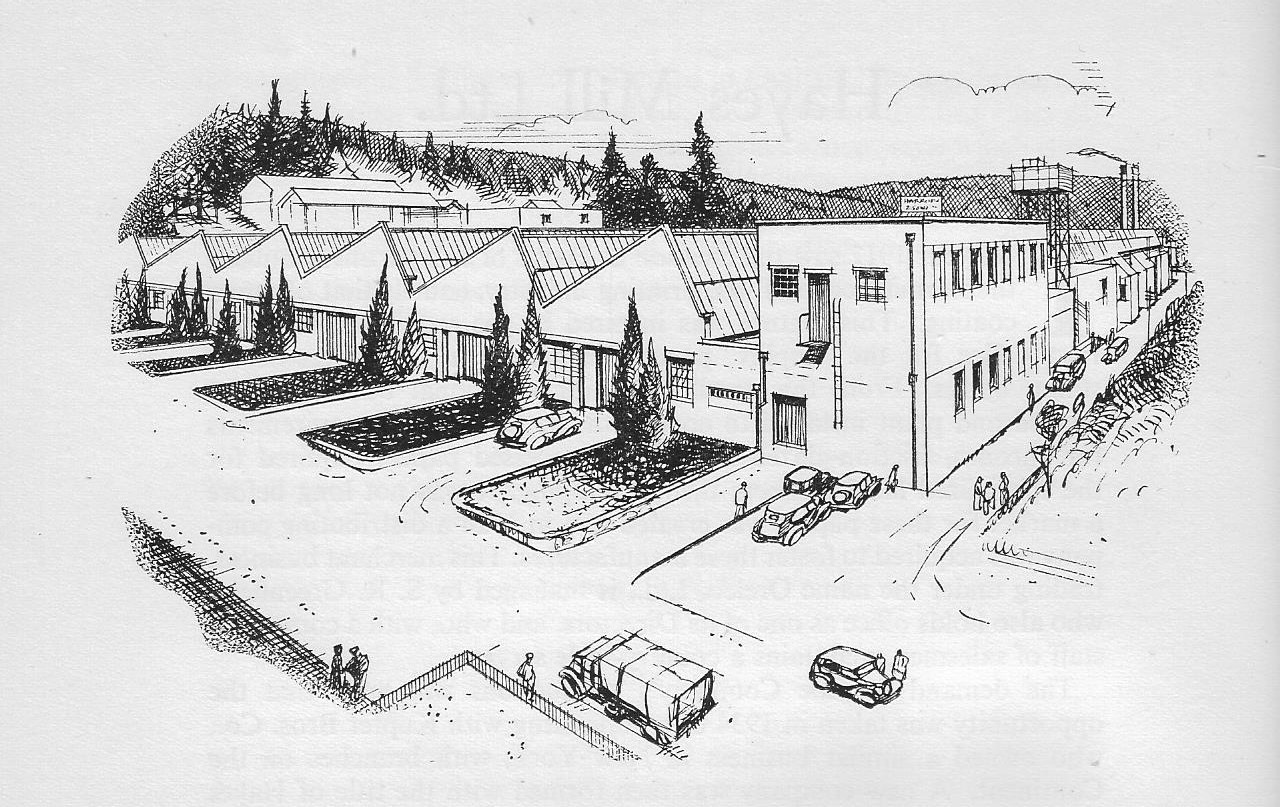

This is a drawing of the factory in the 1950s. taken from the

family Imprint book;

This drawing shows the factory almost as I

first knew it when I joined in 1956.

It shows the original sheds of the Wycombe

Aircraft Constructors and the later added front office block.

The front entrance with the Royal Crest, which

appears in the group picture below, is not yet there.

High Wycombe turned out to be a good choice of location as the war

years loomed up, being out of London and safe from the

bombing. My Uncle escaped conscription to the forces as his job in

postage stamp production was deemed a reserved occupation,

although he was perhaps too old at the start anyway. I

remember in addition to the Stamp printing they must have printed

some comics because he brought me some when he came to visit us in

Northampton. He had moved to a house in Hazlemere, near Wycombe

called Ash Cottage. This was a wonderful house with a large

garden. We used to have holidays there in the War as there was

nowhere else to go, but it was wonderful for me with the garden to

play in and most of all Uncle Jacks Austin 7, laid up in the

garage on blocks for the War duration. I spent hours sitting at

the drivers wheel pretending to drive it. I remember just

everything about it in graphic detail and can still smell

the leather of the seats.

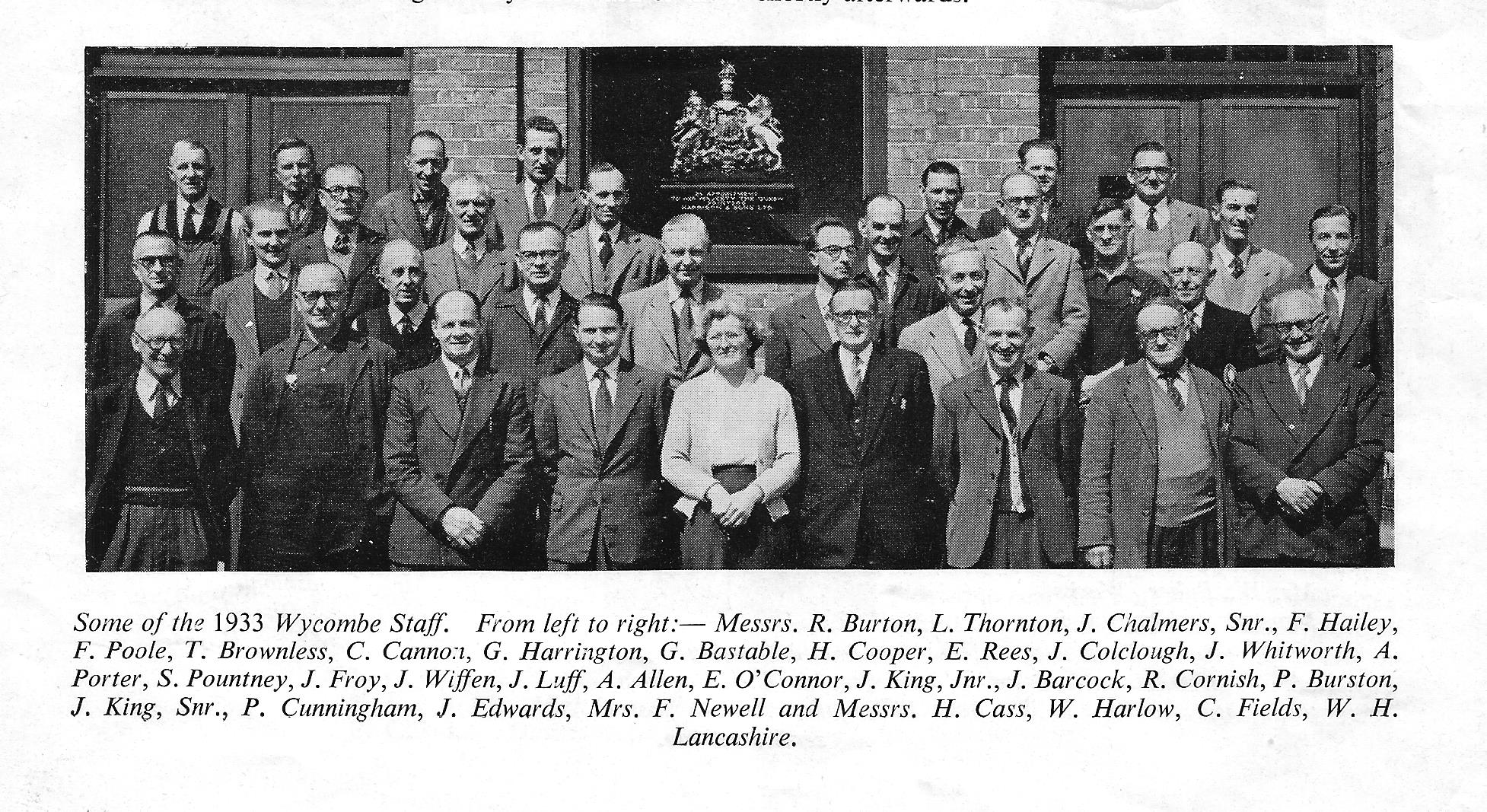

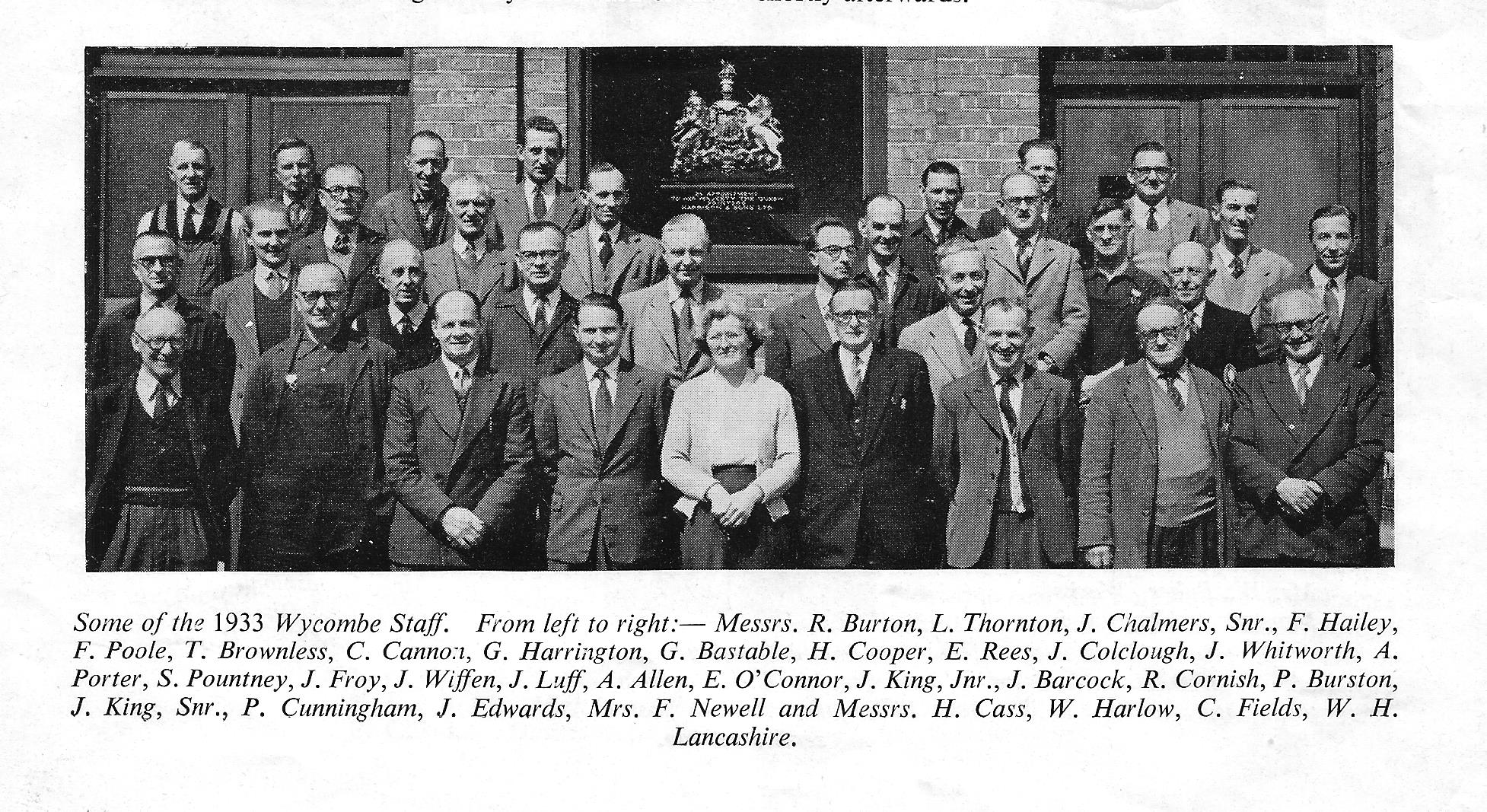

Here is a group Photo from the House Magazine, "Review" of 1958

showing some of the Staff who were with the firm at the start in

1933, outside the front of the factory;

These included most of the men I knew

and worked with when I started in 1956 and who taught me my trade

craft as a photogravure engraver.

These included most of the men I knew

and worked with when I started in 1956 and who taught me my trade

craft as a photogravure engraver.

There is no-one who I can ask permission to use this picture, but

I am sure no-one would object.

Referring here to the men I knew in the left to right order;

L.(Daisy) Thornton, foreman photographic retoucher.

John Chalmers, Snr., Chief Machine minder I believe.

Fred Hailey, Stamp Dept. manager.

Tom Brownless, a dept. manager.

Charles (Charlie) Cannon. Engineering manager.

George Harrington, Camera Operator, Labour Councillor and

Alderman.

George Bastable, Copper Depositing manager.

Harold Cooper, Engraving Foreman, went to NGS School with my

father.

J. (Ted) Colclough, Etching Foreman.

Arthur Porter, Camera Foreman.

Stan Pountney, a dept. manager.

Jack Froy, Machine Minder.

John Wiffen, Planner. I stayed with him and his family when my

Uncle was on holiday.

E (Pat) O'Conner, Carbon Printing foreman and the Union "Father of

the Chapel".

John King, Engraver and my

journeyman for a time. A countryman who went shooting.

Jack Barcock, my wonderful

Uncle.

R (Tom) Cornish, Etcher

John King Snr. Machine

Minder, seen as always in his working overalls.

Harold Lancashire, Chief

Engineer.

The others I remember but

can't recall their jobs.

BACK TO

CONTENTS

4. LIFE AS AN

APPRENTICE

CONTENTS

4.1. INTRODUCTION

4.2. THE FIRST YEAR

4.3. THE TALE

OF THE CHRISTMAS LOAN CLUB

4.4. WILLIAM

(BILL) JEANS, "THE GENERAL"

4.1.

INTRODUCTION

My life as an apprentice started at the moment I signed my

Indentures. My father came to High Wycombe to do this with me. As

an indentured apprentice I would be answerable to my Master so in

a sense my father was handing responsibility for me to him. This

was the nature of apprenticeships in the historical trades and I'm

pleased I have my Indentures as an historical document and record,

but not significant in any other sense now. A copy of the

Indenture document is in my Autobiography Documents

page. I treasure it because it links me to a past tradition of the

industrial age.

The first thing I learned was humility. An apprentice must be

humble and respectful to the journeymen who must be addressed as

"Mr". This might be difficult for a 16 year old who typically

knows everything but fortunately I was not bothered by all this

and had an inbuilt respect for authority from my Grammar School

education and love of Sport which I think teaches respect the

most.

So when I was greeted by one of the great journeyman characters,

"Mac" with the words "So you are the bloody, effing, sodding boy!"

I did not wince at all. The colourful language of print became

part of my vocabulary and is I think a harmless way of dealing

with the disasters of life.

There was an expression for everything, usually profane but

descriptive and sometimes the only satisfactory way to explain the

thing in question. For example, we worked to very fine limits,

tenths of a thou, being ten-thousandth's of an inch, so when

a small difference needed to be made it would be " A gnats cock"

or "Just a fart" being better than "A gnats whisker" or "Just a

sniff". If something like an error in the print stood out it would

be "Like a dogs bollock" or "you've made a right dog's bollock of

that!". The f-word was part of ordinary conversation., such as

"Well f-me" and "That's f-ed it!" The Chief Engineer prefaced

everything with the work "Faarking", a drawn out form of the

adjective! Faarking this and faarking that. The firm put on an

exhibition in the Parish Church one time and the engineers set it

up. One asked "Where shall I put this Chief", to which he replied,

his voice echoing through the Church "Put it by the faarking

Font!".

No disrespect was meant, but it was funny to relate because the

f-word was never used in general conversation outside of the print

environment. Nowadays it is not so shocking and consequently the

humour is somewhat lost. Anyway, I shall not include most of the

profanities in my account, not wishing to cause the reader

offence.

4.2.THE FIRST YEAR

In the first year of my apprenticeship I spent time in each of the

sections of the "process" department. Each section requires

separate skills and I would have to choose my preference and hope

this was accepted. The section operations and skills need some

explanation. I include this brief technical explanation for the

historical interest some may have in the Gravure printing process.

I will try to avoid using the jargon of the trade as much as

possible. Please skip the detail of this part 2.1 it if it proves

too boring!

2.1 The Sections , in order of the stages of the process,

were as follows:

1. Camera Operating. This had "Gallery" cameras of various

sizes and their associated dark rooms for photographic

developing. The cameras ran on rails to enable the original

pictures to be mounted on a copyboard and brought into focus by

rolling the camera on the rails. I don't want to spend a long time

explaining this, except to say the cameras were complex and each

camera operater stuck mainly to his own camera. The largest camera

could take an original 2 or 3 feet square and was heavy to

operate. There were also "Vertical" cameras which saved space. The

product of the camera operating was a glass photographic positive

and then later films, as these eventually replaced glass, with the

correct size picture for the final print.

2. Retouching & Scanning. This was originally an

artistic operation, using hand paintbrushing with dyes to enhance

the appearance or repair or repair faults in the photographic

positives. Then, as the technology advanced they used "masking" by

overlaying the positives with negatives to correct the colour

balance in colour printing. Later still, electronic scanners were

introduced which carried out this "colour correction"

electronically. This complex operation made the retouchers the

most highly paid craftsmen.

3. Planning. This section assembles the photo. positives

into page format and then assembles the pages according to an

imposition scheme to print in correct position for the printing

machine and folder. This fundamental operation of page assembly

according to the printing machine to be used was complicated by

the the large number of different machines, folding methods and

the particular job requirements. My Uncle Jack was planning

foreman and highly respected for his knowledge of the firm's

capabilities and his planning skills. These included glass cutting

when glass positives were used, and the extreme accuracy required

for the "registration" of the four printing colour assemblies in

colour printing.

4. Carbon Printing. In this operation the photographic

images of the page assemblies are transferred to the copper

printing surface, either a copper plate or cylinder. This was done

by exposure in contact with "carbon tissue" using Ultra Violet

"UV" light. The light source was a carbon arc lamp. This would not

be allowed nowadays without shielding, but there was none of that

and the Carbon Printers all had healthy looking tans! They were

actually very unhealthy. The carbon tissue was a gelatin coated

paper sensitised by soaking in potassium dichromate solution

Another very unhealthy operation although heavy rubber gloves were

worn. The sensitised carbon tissue was dried and glazed on glass

plates and cut to the size of the page assemblies for exposure.

The exposed tissue was then transferred to the copper printing

surface using a "laying machine". All this was done in orange

safelight. as the sensitised tissue was only sensitive to UV

light. However, it was also very sensitive to changes in relative

humidity, rh, so the whole are had to be air conditioned to

variation of only + or - 1% rh and 1degree F. An expensive

process.

5. Etching. The copper plates or cylinders were etched,

through the carbon tissue using ferric chloride solutions. The

carbon tissue image had been developed in hot water, the exposure

to the photo positives having hardened it to different

thicknesses. The thinnest parts would be the dark images areas and

the thicker parts the lighter areas. the difference in thickness

being only a few ten-thousand's of an inch, microns in metric

measurement. The rate of etching was controlled by the etcher

using a range of different density ferric chloride solutions, a

highly skilled operation.

The result would be an etched recessed, or intaglio, image that

would hold ink in the printing process.

6. Engraving & Fine Etching. This is the final operation after the

initial proofing of the etched cylinders or plates. It is the

section I joined by choice. Hand engraving appealed to me as

both artistic and uniquely skilful. The fine etching was

interesting too, being the correction of tones in general

printing and balancing the variations across the printed sheet

in the postage stamp printing. The foreman was Harold Cooper, who

my father knew from his schooldays at Northampton Grammar School

for Boys. There were some very skilled hand engravers, some had been banknote

engravers.

7. Copper Depositing, Polishing and Chrome Plating. This

ancillary section to the main process involved the preparation of

the copper cylinders for the Carbon Printers, and the finishing of

the cylinders by chromium plating to increase the wearing

resistance. This involved electro-deposition of copper on a steel

base, polishing the copper surface to a perfectly smooth finish.

Then, after etching, chromium plating by electro-deposition.

All these operations required great skill and knowledge of the

Gravure process and I still wonder at how these skills were

developed and how they have mostly disappeared now after existing

for so many years.

4.3. THE

TALE OF THE CHRISTMAS LOAN CLUB

Perhaps my first realisation of the nature of the firm I was

working for came from a remarkable series of events

involving the Christmas Loan Club. Loan clubs were a popular way

of saving money and getting small loans when needed. You have to

remember there were no such things as credit cards, let alone Pay

Day loan companies. It was a way of saving for Christmas usually

which involved putting in a regular amount, and if a loan was

taken out, paying it back with interest. At Christmas, the

interest was shared out among the members with the money they had

saved depending on how much they had paid in. Money paid in was by

buying shares using a 'paying in' book.

Variations on this were organised by clubs and pubs as well as

employees of firms. There were often examples of the treasurers of

pubs and clubs being overcome by temptation, debt or gambling,

losing the loan clubs money and finishing up in gaol! This

happened to Diane's parents when the landlord of the pub Christmas

loan club they were in lost them their money.

On hearing this I boldly told them I would take some shares out

for them with Harrisons loan club for the next Christmas, which

would be as safe as houses.

Of course, the inevitable happened, as follows;

The loan club issued savings cards with Harrison & Sons Loan

Club on the front as records of members contributions, but the

club was entirely run by by its members having appointed officials

to administer the records and bank the monies. I think

contributions could be stopped from members wages or paid in cash

and the accounts were kept by the appointed Secretary who I

believe was an accountant in the wages office. ( I may have some

details incorrect here, but the story in essence is not affected

by that).

When the end of year accounts were completed a couple of officials

who were I think Ted Colclough, the Etching department foreman,

accompanied by the aforementioned Mac, who was ex Royal Artillery

Captain, acting as bodyguard, went to collect the cash from the

bank on Frogmore Square in High Wycombe. Mac sat in the car ready

for all eventualities except the one Ted brought back to him from

the bank. This was the the money had all been drawn out a few days

earlier by the Secretary!

When they returned to confront the Secretary they discovered he

was not at work and also was not at home either. Eventually his

bicycle and clothes were found abandoned by the Thames at Marlow

and everyone feared the worst. People's reactions were a mixture

of anger and concern for him and his family. I myself realised I

would have to tell Diane's parents their Christmas savings were

lost again Something I did not relish doing.

A meeting was called in the works canteen of all loan

club shareholders and we all made our way to there after work. It

was a very noisy, somewhat bad tempered and worried congregation.

The loan club officials and some members of the management

including Hugh Harrison appeared on the stage. One of the

officials confirmed that the money had gone and was lost, but Mr.

Hugh had something to say. Hughie, as he was affectionately

called, explained, (in his rather high, almost falsetto voice)

that, although the name of Harrisons appeared on the shareholders

card, the company had no legal responsibility for the losses. This

produced a very disgruntled murmur, but he continued ( I

paraphrase) "However we feel a moral responsibility and will

refund all the lost monies". Wow! A stunned silence seemed to last

ages before a cheer and clapping broke out.

I breathed a sigh of relief myself as I now had good news for my

future In-Laws.

The secretary was discovered in Ireland to everyone's relief and

brought back to Wycombe to stand trial. Harrisons gave evidence of

his previous good character and I believe he was released and

later re-employed by the Company. Just like the return of the

Prodigal Son to the family. What a wonderful happy ending due

indeed to the special nature of the firm.

4.4. WILLIAM

(BILL) JEANS, "THE GENERAL"

General Jeans was my designated Journeyman for a time which

meant that I worked with him to learn his special part in the

engraving and revision process.

He was a great character with an almost unbelievable background

and when he passed away I visited his wife who gave me his

engraver's toolbox which I still have with some of his tools.

He always referred to his wife as "Mrs. Jeans" which explains his

character exactly. I never knew her first name. He got the

nickname "General" because he had been in the South African Police

at one time, not a General, but had some rank of authority. he

showed us pictures of him in uniform and with his native servants.

What he was doing in the South African Police I'm not

sure, but he had a rather roguish nature and I think he

may have used it to escape being called up for the

forces.

He was an ideal target for the jokers who liked to get a reaction

from him. One of these who was expert in winding him up had a

photo in a magazine we were printing to show him. It was of a

group of native Africans. He said "Mr. Jeans, you were in South

Africa weren't you?"

The General answered rather proudly, "That is correct, I spent

some years in the South African Police".

"Then, do you recognise any of these chaps?" showing him the

picture. He took the picture, looked at it, and exploded "You

bloody fool, there were millions of them!"

He also lived in Paris for a while, probably working

as an engraver somewhere, and spoke fluent French. He came in

one day and said " I fooled a caller yesterday who came to the

house selling something. I leaned out of the upstairs window

and addressed him in French, then went down and opened the

door and asked him what he wanted. He looked at me and said",

"Where is that French gentleman I just spoke to?" He was

absolutely amazed when I said "I am he!".

Cue for the Joker to say "Mr. Jeans, is it true you once lived

in Paris?"

As expected he replied "That is correct, I lived there some

years".

"Then, do you remember a street called the "Rue de Postcard?".

The General mused for a few seconds repeating "Rue de

Postcard" Then exploded "You bloody fool..... etc. etc."

This formula was repeated over and over with the same result

every time!

His main task was fine etching the stamp cylinders. This was

to balance up variations in the strength of the printed image

across the sheet of 2 x 240 stamps.

Harrisons

is

at

the

right top next to Hughenden Park where the trees and stream can be

seen.

Harrisons

is

at

the

right top next to Hughenden Park where the trees and stream can be

seen.

These I understand from

Peter Tozer and some research I have done were the sheds used by

the "Wycombe Aircraft Constructors" company. These date from at

least 1917 when the company was set up to manufacture parts for

aircraft, particularly in WW1, by George Holt Thomas of Wycombe.

He set up a company called Airco in Hendon in 1912 and employed

the famous Geoffrey de Havilland as chief designer.

These I understand from

Peter Tozer and some research I have done were the sheds used by

the "Wycombe Aircraft Constructors" company. These date from at

least 1917 when the company was set up to manufacture parts for

aircraft, particularly in WW1, by George Holt Thomas of Wycombe.

He set up a company called Airco in Hendon in 1912 and employed

the famous Geoffrey de Havilland as chief designer.

These included most of the men I knew

and worked with when I started in 1956 and who taught me my trade

craft as a photogravure engraver.

These included most of the men I knew

and worked with when I started in 1956 and who taught me my trade

craft as a photogravure engraver.